Joanna Macy on: The Tree Stories of our Time

1. Business as usual

One way of thinking about our times is that we are enacting a wonderful success story. Economic and technological development has made many aspects of our lives easier. If we ‘re looking at how to move forward, the path this story suggests is “more of the same, please.” We ‘re calling this story Business as Usual. This is the story told by most mainstream policy makers and corporate leaders. Their view is that economies can, and must, continue to grow. Even in the face of economic downturns and periods of recession, the dominant assumption is that it won’t be long before things pick up again.

Expressing his trust in the path of economic growth‘ in November 2010 President Obama said, “The single most important thing we can do to reduce our debt and deficits is to grow.”

For a market economy to grow, it needs to increase sales. That means encouraging us to buy, and consume, more than we already do. Advertising plays a key role in stimulating consumption, and increasingly children are targeted as a way of boosting each household’s appetite for goods. Estimates suggest that the average American child watches between twenty-five thousand and forty thousand television commercials a year. In the United Kingdom, it is about ten thousand.’

As we grow up, we learn by watching ethers. Our views about what‘s normal and necessary are shaped by what we see. When you’re living in the middle of this story, it’s easy to think of it as just the way things are. Young people may be told there is no alternative but to find their place in this scheme of things. Getting ahead is presented as the main plot, supported by the subplots of finding a partner, fending for your family, looking good, and buying stuff. In this view of life, the problems of the world are seen as far away and irrelevant to the dramas of our personal lives.

Economic growth is essential for prosperity

Nature is a commodity to be used for human purposes

Promoting consumption is good for the economy

The central plot is about getting ahead

The problems of other peoples, nations, species are not our concern.

2. THE SECOND STORY: THE GREAT UNRAVELING

In 2010 polls for both CBS8 and Fox News9 showed that a majority believed the conditions for the next generation would be worse than for people living today. Two years earlier, an international poll of more than 6I,600 people in sixty countries yielded similar results. With so many people losing confidence that things will be okay, a very different account of events is emerging. Since it involves a perception that our world is in serious decline, we take a term used by social thinker David Korten and call this story the Great Unraveling.”

In our work with people addressing their concerns about the world, we‘ re struck by how many issues are triggering alarm.

Five common areas of concern, and most likely you have some others you would add to this list. Facing these problems can feel uncomfortable, even overwhelming, but in order to get to where we want to go, we need to start from where we are. The story of the Great Unraveling offers a disturbing picture of where that is.

The Great Unraveling of the Early Twenty–First Century

Economic decline

Resource depletion

Climate change

Social division and war

Mass extinction of species

Amazone, S. America, free picture internet

3. The Third Dimension: Shift in Consciousness

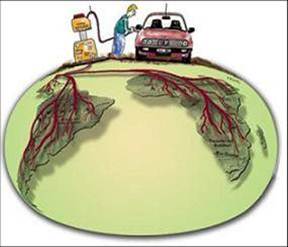

What inspires people to embark on projects or support campaigns that are not of immediate personal benefit? At the core of our consciousness is a wellspring of caring and compassion; this aspect of ourselves– which we might think of as our connected se/f- can be nurtured and deve1oped. We can deepen our sense of belonging in the world. Like trees extending their root system, we can grow in connection, thus allowing ourselves to draw from a deeper pool of strength accessing the courage and intelligence we so greatly need now. This dimension of the Great Turning arises from shifts taking place in our hearts, our minds, and our views of reality involves insights and practices that resonate with venerable spiritual traditions while in alignment with revolutionary new understanding from science.

A significant event in this part of the story is the Apollo 8 space flight of December 1968. Because of this mission to the moon, and the photos it produced, humanity had its first sighting of Earth as a whole. Twenty years earlier, the astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle had said, “Once a photograph of the Earth taken from the outside is available, a new idea as powerful as any in history will be let loose.” Bill Anders, the astronaut who took those first photos commented, “We came all this way to explore the moon and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

We are among the first in human history to have had this remarkable view. It came at the same time as the development in science of a radical new understanding of how our world works. Looking at our planet as a whole, Gaia theory proposes that the Earth functions as a self-regulating living system.

During the past forty years, those Earth photos, along with Gaia theory and environmental challenges, have provoked the emergence of a new way of thinking about ourselves. No longer just citizens of this country or that, we are discovering a deeper collective identity,

As many indigenous traditions have taught for generations, we are part of the Earth. A shift in consciousness is taking place, as we move into a larger landscape of what we are. With this evolutionary jump comes a beautiful convergence of two areas previously thought to clash: science and spirituality. The awareness of a deeper unity connecting us lies at the heart of many spiritual traditions; insights from modern science point in a similar direction. We live at a time when a new view of reality is emerging, where spiritual insight and scientific discovery both contribute to our understanding of ourselves as intimately interwoven with our world.

We take part in this third dimension of the Great Turning when we pay attention to the inner frontier of change, to the personal and spiritual development that enhances our capacity and desire to act for our world. By strengthening our compassion, we give fuel to our courage and determination. By refreshing our sense of belonging in the world, we widen the web of relationships that nourishes us and protects us from burnout. In the past, changing the self and changing the world were often regarded as separate endeavours and viewed in either–or terms. But in the story of the Great Turning, they are recognized as mutually reinforcing and essential to one another.

free picture NASA

ACTIVE HOPE AND THE STORY OF OUR LlVES

Future generations will look back at the time we are living in now. The kind of future they look from, and the story they tell about our period, will be shaped by choices we make in our lifetimes. The most telling choice of all may well be the story we live from and see ourselves participating in. It sets the context of our lives in a way that influences all our other decisions. ‘ In choosing our story, we not only cast our vote of influence over the kind of world future generations inherit, but we also affect our own lives in the here and now. When we find a good story and fully give ourselves to it, that story can act through us, breathing new life into everything we do. When we move in a direction that touches our heart, we add to the momentum of deeper purpose that makes us feel more alive. A great story and a satisfying life share a vital element: a compelling plot that .moves toward meaningful goals, where what is at stake is far larger than our personal gains and losses. The Great Turning is such a story.

- J. Macy, Active Hope, Chapter One The Three Stories of Our Time. Page 13-33 ISBN 978 1577 319726

- www.joannamacy.net Link to her website.please.